Imagine this: You retire with a $1,000,000 portfolio invested in the S&P 500. You expect to withdraw 4% each year to fund your lifestyle. This should be no problem because the index returns 10% each year. However, right you retire, the markets drop 30%. Your portfolio is your main source of income so you go ahead and withdraw $40,000. Your portfolio is now $660,000. A year goes by a the markets have fallen again by 5%. You need more money so you take out another $40,000 (now a 6.4% withdrawal rate) bringing your balance down to $597,000 - almost half of what you started with just 1 year prior. This is what you would have faced, relatively speaking, if you retired in 1999 (Dot-Com Crash), 2007 (Great Recession), or more recently 2019 (Covid). In this post, I'll detail a withdrawal strategy that will help you avoid running out of money as well as boosting your income from the standard 4% rule.

Why Is Withdrawing From A Portfolio Hard?

Before we go over this strategy let's explain why we need it.

Sequence of return risk

Like I mentioned above, the S&P 500 averages about 10% each year. If each year you made exactly 10% on your money, withdrawing money would be easy. Each year you would subtract the annual return (10%) from the inflation of that year (let's assume 3% for this example), and that is the percent of your portfolio you would withdraw. If you had $1 million you would take out $70,000.

Unfortunately (or fortunately depending on if you're accumulating wealth!), the S&P 500 is not constantly moving upwards. Some years it will lose value; sometimes lot's of it. In fact, the S&P 500 has never returned its average yearly return of 10% exactly in a single year. The example in the introduction is an example of sequence of return risk.

Guyton-Klinger Guardrails

Introducing the Guardrails approach to retirement spending. This approach was first published in 2004 by Jonathan T. Guyton1 and then again in a follow up paper in 2006 by Guyton and William J. Klinger2. The 2006 paper was an improvement over the original paper and the one we'll be focusing on today.

In the paper, Guyton and Klinger try to develop an approach for living off your portfolio without running out of money. They were trying to create a strategy that allowed for the following:

- 40 year withdrawal period to account for longer lifespans

- Maximize the amount you can withdraw each year

To answer these questions, they looked at past data and ran simulations. In the end, they came up with 5 rules to follow when withdrawing money from your portfolio.

The rules are as follows:

- Portfolio Management Rule (PMR)

- Inflation Rule (IR)

- Withdrawal Rule (WR)

- Capital Preservation Rule (CPR)

- Prosperity Rule (PR)

By following a combination of these rules we can be sure our portfolio can sustain an initial withdrawal rate between 5.2% – 5.6% for 40 years.

Let's dive deeper into each of these rules.

Portfolio Management Rule (PMR)

The first rule of this plan determines where we will pull money from. Take a look at the excerpt from the paper:

- Following years where an asset class has a positive return that produced a weighting exceeding its target allocation, the excess allocation is sold and the proceeds invested in cash to meet future withdrawal requirements.

- Portfolio withdrawals are funded in the following order: (1) overweighting in equity asset classes from the prior year-end, (2) overweighting in fixed income from the prior year-end, (3) cash, (4) withdrawals from remaining fixed-income assets, (5) withdrawals from remaining equity assets in order of the prior year's performance.

- No withdrawals are taken from any equity following a year with a negative return if cash or fixed-income assets are sufficient to fund the required withdrawal.

Let's look at an example to understand this rule. Imagine your portfolio is 65% equities (stocks), 30% fixed income (bonds), and 5% cash. If after one year equities go up 10% and bonds drop 5%, your new allocation would be 68% equities, 27% fixed income, and 5% cash. Because your equities went up, you would withdraw from that. If instead equities went down 10% and fixed income went down 1%, you would take from cash. If you had no cash and equities and fixed income were both negative for the year, you would take from fixed income. If there is no remaining fixed income, you take from the equities that have lost the least.

Inflation Rule (IR)

Each year things get more expensive. The exact percentage is detailed in the CPI report. The inflation rule determines the size of the yearly withdrawal increase to match inflation. Again, let's look at an excerpt from the paper describing this rule:

- Yearly withdrawals increase by the annual rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) except when the withdrawal rule freezes the withdrawals.

- The maximum annual inflationary increase is 6 percent.

- There is no "make-up" for a "capped" inflation adjustment.

This rule is pretty simple. Whatever amount inflation increases by, you can increase your withdrawal rate by that amount up to 6%. Imagine you took $50,000 out of your $1 million portfolio. This is 5%. If inflation increases 5%, the next year you would take out $52,500 (50,000 x 5%).If your portfolio balance stayed the same at $1 million, this would represent a withdrawal rate of 5.25%. This will be important for the next rule.

Also note there is no make up for capped inflation. For example if inflation is 8% one year and 2% the next, you can't take the remaining 2% that was capped the first year and add it to the following year by increasing withdrawals by 4%. You can only do 6% and 2%.

Withdrawal Rule (WR)

This determines the conditions when portfolio withdrawals are frozen from one year to the next. An excerpt from the paper:

- Withdrawals increase from year to year in accordance with the inflation rule, except that there is no increase following a year where the portfolio's total return is negative.

- There is no "make-up" for a missed increase.

In the last rule we saw how we are allowed to adjust our withdrawals by inflation. The Withdrawal rule states that if the portfolio is down (or even flat) and our withdrawal rate is greater than our initial withdrawal rate we cannot increase our withdrawal rate. Going back to the last example, our initial withdrawal rate was 5%. With the inflation increase it became 5.25%. This would be disallowed according to this rule. In this case we would continue to take $50,000 for the next year until our portfolio can recover.

Capital Preservation Rule (CPR)

Now we are getting to why this is called The Guardrails Approach. This rule allows you to make adjustments to your withdrawal rate. It's the reason we can start with a higher withdrawal rate. This is an excerpt from the paper:

- The capital preservation rule applies when a current year's withdrawal rate—using the decision rules in effect—has risen more than 20 percent above the initial withdrawal rate.

- The capital preservation rule expires 15 years before the maximum age to which the retiree wishes to plan; for example, a retiree assuming she would not live beyond age 100 would discontinue the capital preservation rule after age 85.

- Under the capital preservation rule, is the current year's withdrawal is reduced by 10 percent. The other decision rules in effect are then applied to this decreased withdrawal amount.

- This decreased withdrawal becomes the basis for determining the following year's withdrawal amount.

In essence, if your withdrawal rate gets too high you need to take a temporary cut from your portfolio. Your withdrawal rate can get higher if your portfolio drops in value or if you are simply spending more. Doing some quick math, if your initial withdrawal rate is 5% and now it is 6%, that is a 20% increase. This rule would tell us to take a temporary cut down to 5.5%.

Prosperity Rule (PR)

This rule is the opposite of the CPR rule. Markets down only go down a ton, sometimes they go up a ton. From the paper:

- The prosperity rule applies in years with a withdrawal rate more than 20 percent below the initial withdrawal rate.

- Under the prosperity rule, the current year's withdrawal is increased by 10 percent. The other decision rules in effect are then applied to this increased withdrawal amount.

- This increased withdrawal amount becomes the basis for determining the next year's withdrawal.

Simply put - If your portfolio is doing well, you are allowed to give yourself an increased withdrawal rate.

What About The Failed Simulations

If you follow these rules, there is a good chance your portfolio will give you enough money for 40 plus years. However, there are scenarios in the paper where these rules failed. Let's go over at what the authors found. I think you'll find these results fairly intuitive.

The Perfect Storm

Failures in the study were most likely to occur when investment returns were abnormally low, inflation was abnormally high, or both of these things happened at the same time for an extended period of time early in retirement. This is exactly why the Capital Preservation Rule was created. Instead of stopping withdrawals in times of a market decrease, we decrease them. This allows the principle to not get drawn down too much and when the market recovers, we increase the withdrawal rates again.

Conclusion

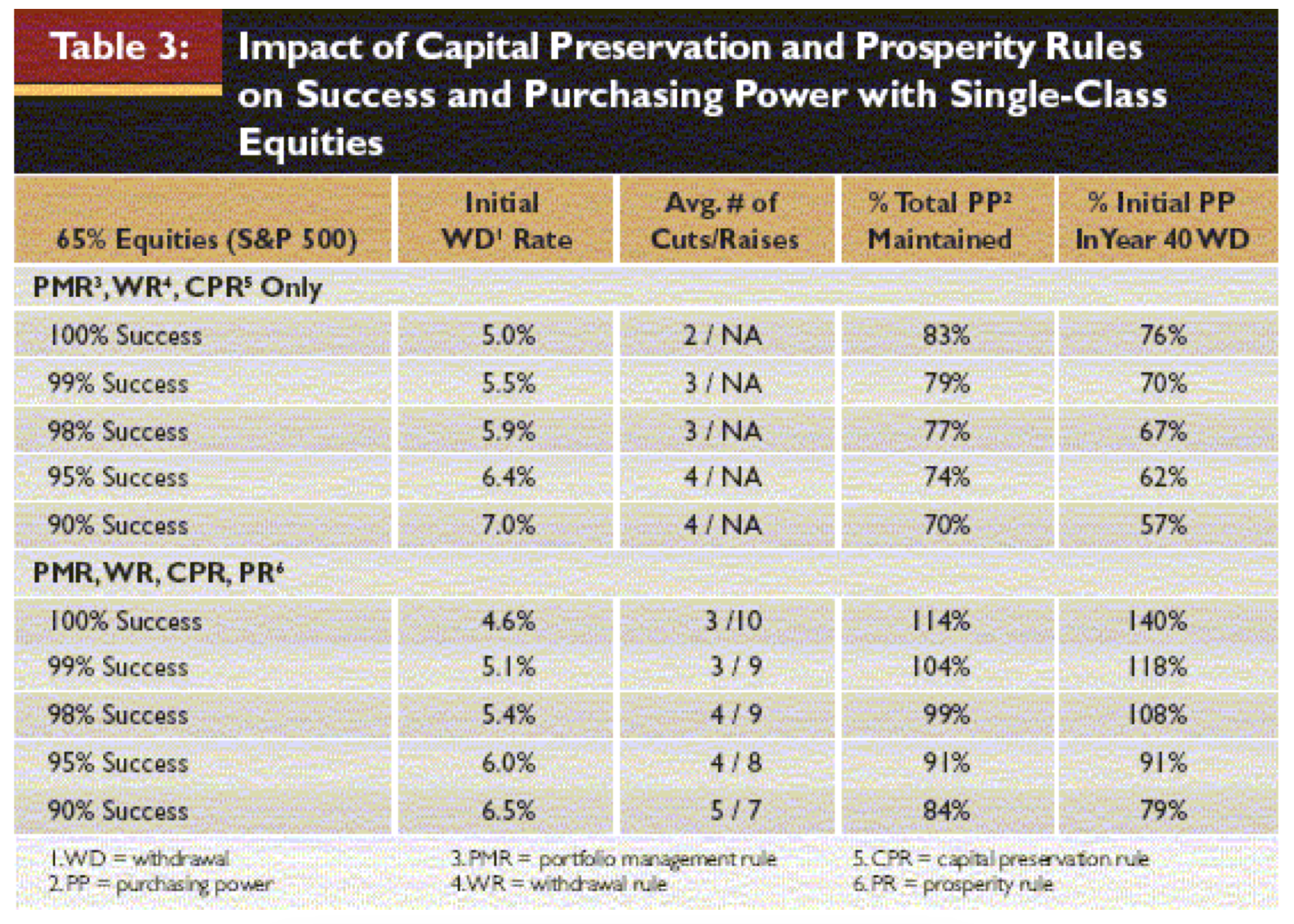

We've talked a lot about these rules and given some examples along the way. Let's take a look at a chart that shows these rules in action along with the initial withdrawal rate and the success.

All of these rules can be summed up like such:

- Portfolio Management Rule (PMR)

- Pull money in the order of best performers, cash, fixed income, what went down the least.

- Inflation Rule (IR)

- Increase withdraws each year by the CPI level but no more than 6%.

- Withdrawal Rule (WR)

- If portfolio is down, no increase in withdraws for the next year.

- Capital Preservation Rule (CPR)

- If portfolio declines too much in value, take less.

- Prosperity Rule (PR)

- If portfolio grows faster than expected, take more.

By following these rules you should be able to have initial withdrawal rates of 5.2% – 5.6% with 99% confidence you will not run out of money for 40 years with a portfolio of 65% equities.